Millions of gallons of oil settled at the bottom of the golf after BP oil spill

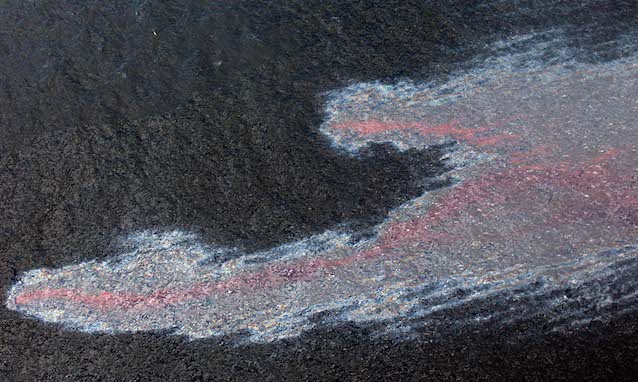

An oil slick sits on the surface of the water a few miles from the site of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico Saturday, July 17, 2010.

… CREDIT: AP Photo/Dave Martin

By Katie Valentine Posted on January 30, 2015 at 3:01 pm

Millions of gallons of oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill didn’t get cleaned up, and instead settled in the sediment of the Gulf of Mexico’s floor, a new study has found.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, found that 6 to 10 million gallons of oil from the spill are buried in the seafloor. The researchers measured the amount of carbon 14 — a radioactive carbon isotope that’s found in organic material but not found in oil — in an approximately 24,000 km² area of sediment near the spill site, a process which allowed them to see what parts of the sediment were low in carbon 14 and thus contained oil.

The study sought to determine two things: whether oil had, in fact, settled on the seafloor, and how much of it had settled. Jeff Chanton, Professor of Oceanography at Florida State University and lead author of the study, told ThinkProgress that he had thought the total amount of oil they would find at the ocean floor would be higher, because after the spill, so many people had observed the oil clumping at the water’s surface and sinking.

Regardless of the amount, however, Chanton said that sedimentation was a “new phenomenon” that hadn’t been heavily observed or studied after previous oil spills.

“Everyone thinks oil is very buoyant and that it just floats on the surface,” Chanton said. So in the past, sedimentation of oil hasn’t been a main concern for scientists and cleanup workers. The federal Oil Budget Calculator, which was developed to determine where the oil of the Deepwater Horizon spill ended up in the short term, didn’t include efforts to figure out how much of the oil ended up in the Gulf’s sediment.

The researchers found that the oil was buried in the top layers of the Gulf’s sediment, meaning that if the sediment is stirred up in the future, the oil could once again enter the water. Chanton said the oil’s position on the sediment’s surface also means that it’s a part of the food chain: the worms and other benthic organisms that live on the seafloor and feed on sediments will ingest the oil, and the contaminants associated with the oil will be passed on to the creatures that eat the worms. That could be a long-term problem for the health of these Deepwater Gulf fish, Chanton said.

Chanton’s study isn’t the first to look at sedimentation after the Deepwater Horizon spill. Last fall, a study found the spill had left a 1,235-square-mile “bathtub ring” of oil on the ocean’s floor. And last May, after a group of researchers spent about a month in the Gulf, one of them — Andreas Teske, marine sciences professor at the University of North Carolina — told ThinkProgress that the oil on the bottom of the seafloor is becoming “part of the geological record.”

“Since one cannot take a gigantic vacuum cleaner and clean up this stuff, getting buried is the best alternative,” Teske said.

Oil’s been found to have gathered in sediment closer to shore too: last year, a 1,250-pound tar mat was discovered off the beach of Santa Rosa Island, Florida.

Chanton’s study comes amid the third and final stage of BP’s civil trial for the spill. Earlier this month, an expert witness for BP testified that the Gulf’s shoreline had shown “substantial recovery” since the spill, and that BP’s work to clean up the oil had been “comprehensive” and “effective.” A BP executive also claimed in Politico last year that his company “didn’t ruin the Gulf.” But Chanton’s study — and previous studies on the health of the Gulf post-spill — shows that though beaches might be cleaner than they were four years ago, the spill’s lasting impact on the Gulf has yet to be determined.